Labor Day is one of those holidays where if you stopped the average person on the street, they might struggle to explain its meaning. To refresh: it originated from the fight for the eight-hour workday and better working conditions in the late 19th century. Over time, it evolved into a broader celebration of workers’ contributions to American prosperity. Which makes today a little ironic and/or outdated when labor seems increasingly disconnected from the wealth it’s meant to create: stock valuations soar whilst wages stagnate and unemployment rises—a seemingly impossible combo when we assumed prosperity flowed to both labor and capital.

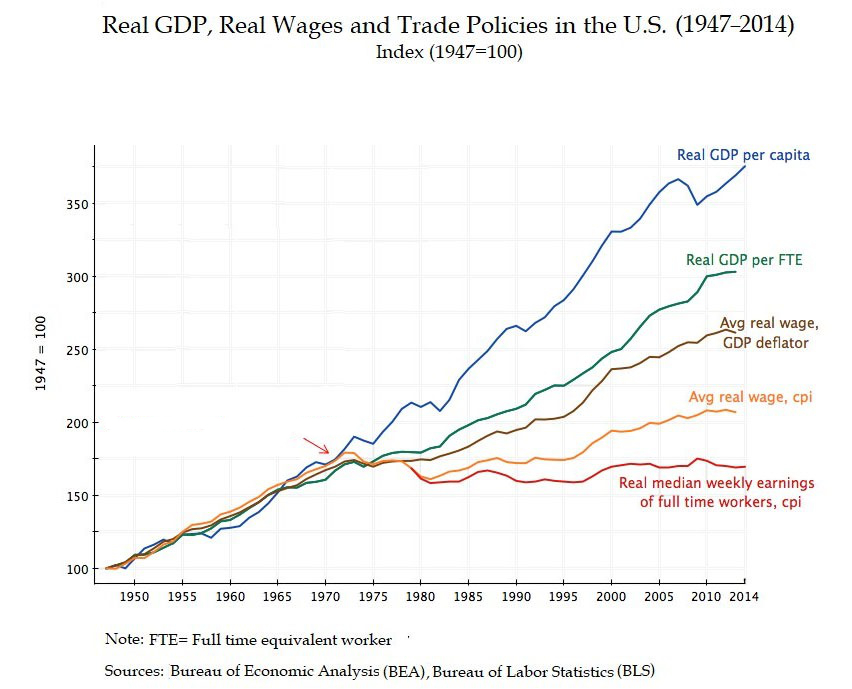

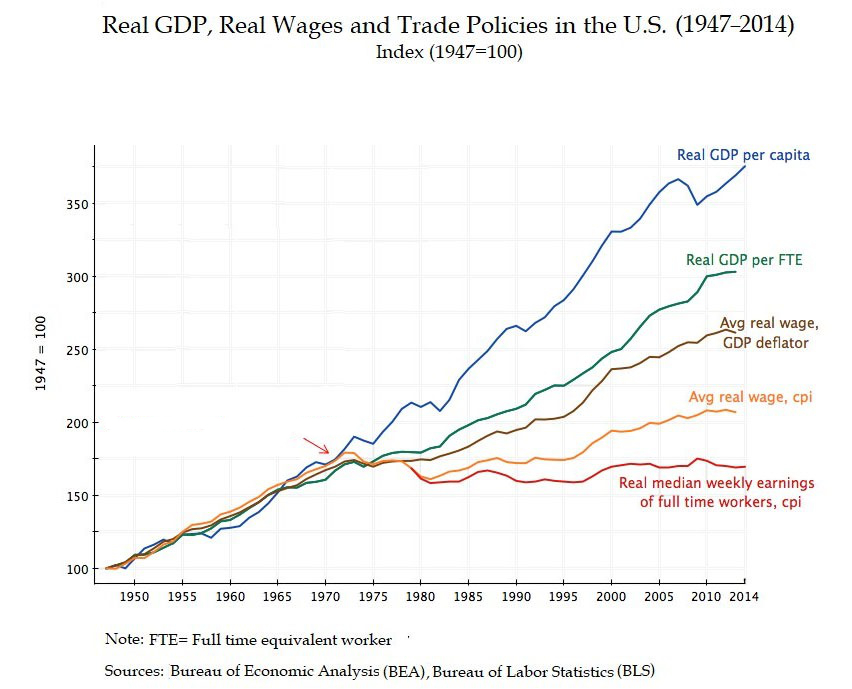

The empirical foundation of labor-capital disconnection is the “Great Decoupling”1 which describes the post-1970s divergence between productivity, GDP growth, and median wages; but you know it better as the wtfhappenedin1971.com meme:

Plenty of factors influence valuations and the capital markets, but some of the reasons labor plays a diminishing role:

It’s still early innings, but AI has the potential to spell the most significant acceleration of labor-capital disconnection in history once adoption reaches scale. Recent empirical evidence suggests current job displacement effects remain modest3, but the structural conditions are being set for dramatic future impact. As AI adoption accelerates beyond the current 9% of businesses using it in production, we should expect wealth polarity to increase dramatically when AI separates those who can marshal the tools and benefits of AI from the have-nots (the ‘hollowing out’ hypothesis4). Of course, inequality is no new phenomenon (it’s a feature of a capitalism5), but AI may be an accelerant for capital owners (where ownership is highly concentrated among a few major tech companies) and high-skill workers6.

What are we going to do about it? Some kind of restructuring of ownership / wealth redistribution (e.g., UBI, sovereign wealth funds)? Elite capture suggests probably not. Hopefully, we will at least reinvest in society by reimagining our education system, though this assumes the problem is skills mismatch rather than systemic capital concentration.

Of course, there will be shifts in labor toward AI resistant markets (e.g., plumbing, therapy, interior design, childcare), and current data suggests most workers aren’t yet seeing displacement—but while celebrating the worker today, we need to think about whether individual adaptation can address what may become a fundamental shift in how value gets created and distributed as AI adoption scales.

Happy Labor Day,

— ᴘ. ᴍ. ʙ.

Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, Race Against the Machine: How the Digital Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy (Lexington, MA: Digital Frontier Press, 2011). ↩

Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017). ↩

Sarah Eckhardt and Nathan Goldschlag, “AI and Jobs: The Final Word (Until the Next One),” Economic Innovation Group, August 10, 2025. ↩

Middle-skill jobs disappear while low-skill service jobs and high-skill knowledge work remain, creating labor market polarization. David H. Autor, Lawrence F. Katz, and Melissa S. Kearney, “The Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market,” American Economic Review 96, no. 2 (May 2006): 189-194. ↩

Piketty’s r > g formula: when the return to capital (r) exceeds economic growth (g), wealth concentrates among capital owners regardless of labor productivity. Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014). ↩

There’s a labor economics theory called “skill-biased technological change” (SBTC) that explains how technology complements high-skill workers while substituting for others, creating winner-take-all dynamics that benefit capital and a small labor elite. ↩

First published: 2025-09-01 | tweet | cast | subscribe