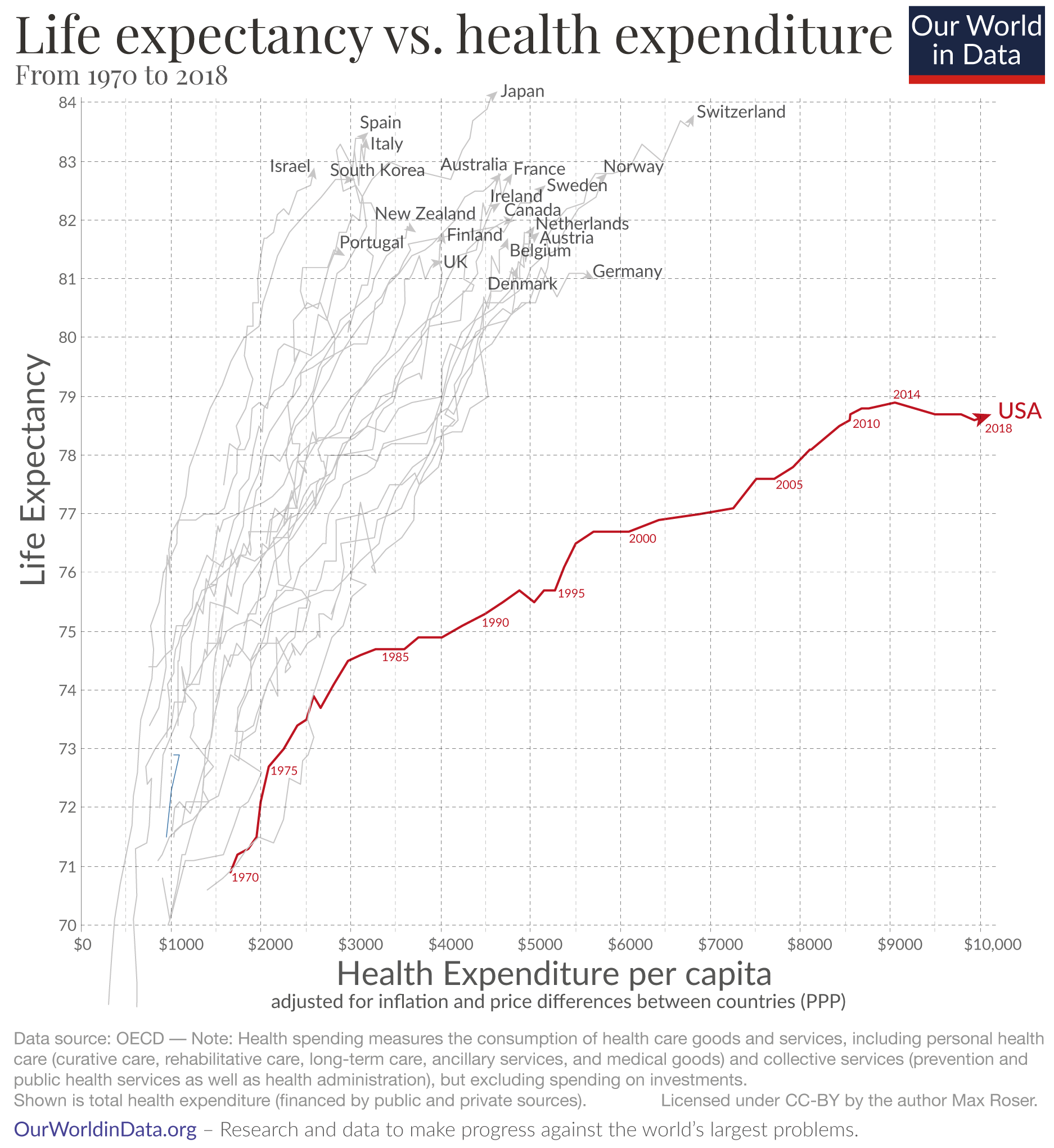

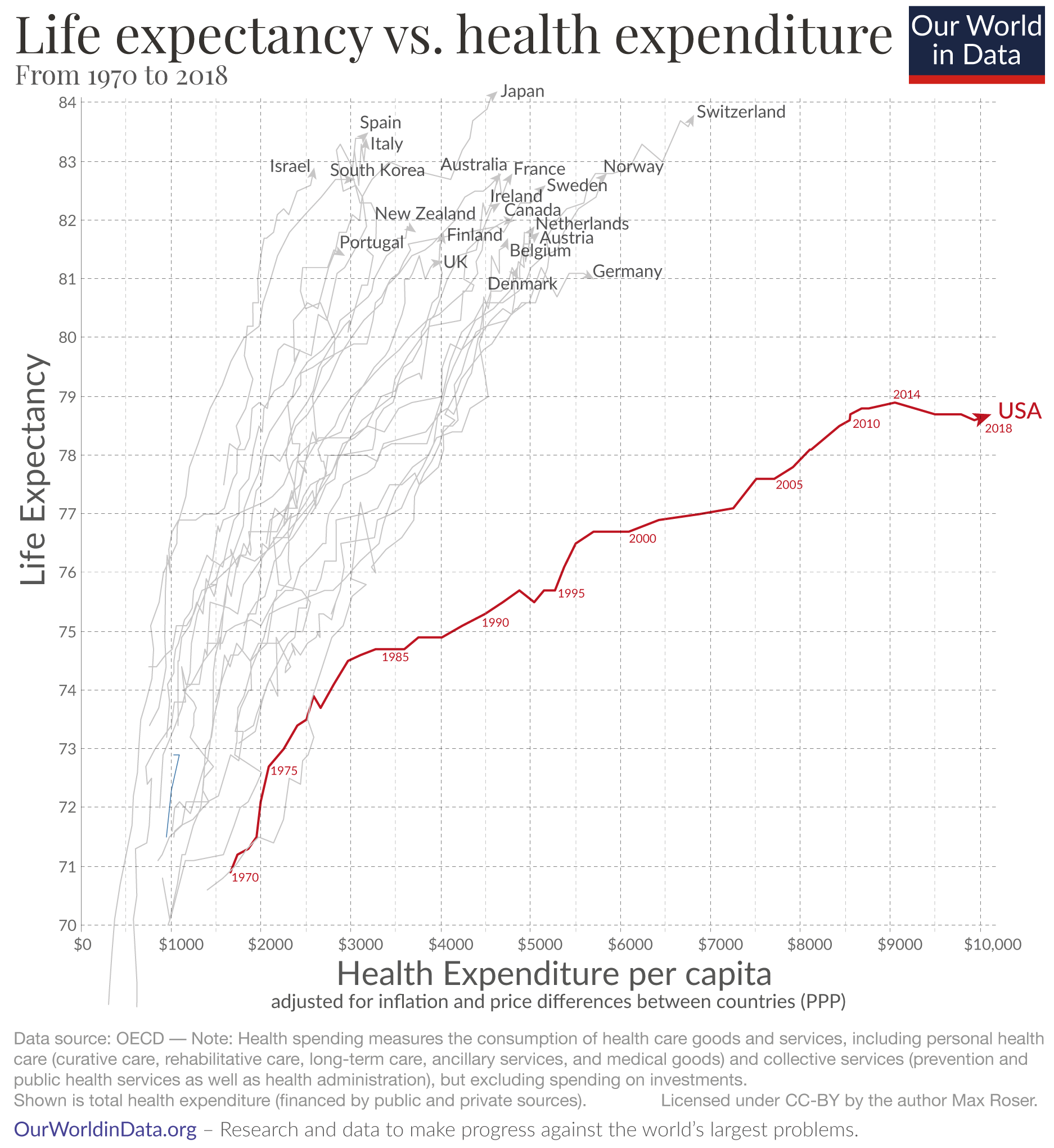

I attended a talk yesterday on health economics in the US market, and the lecturer trots out this sequence of slides that first show how much the US spends on healthcare (in total and per capita) and then our below-average life expectancy (when compared with wealthier peer countries).

But as she spoke it got me wondering: what portion of the delta in life expectancy can be explained by our healthcare system versus factors outside of it?

So I had to look into it, and firstly, it is true that these two regrettable facts often come as a pair: the U.S. having the lowest life expectancy amongst its wealthier peer countries and that it far outspends them on healthcare; the implication being that our healthcare system is so broken, that we can’t even spend our way to average life expectancy.

And it’s not just this professor; the CDC links them as well, and defines the intersection as “health disadvantage”1:

People in the United States have poorer health, more illness, and shorter lives than people in other wealthy countries. Americans pay too much for healthcare and lack adequate access to healthcare. This is called the U.S. health disadvantage.

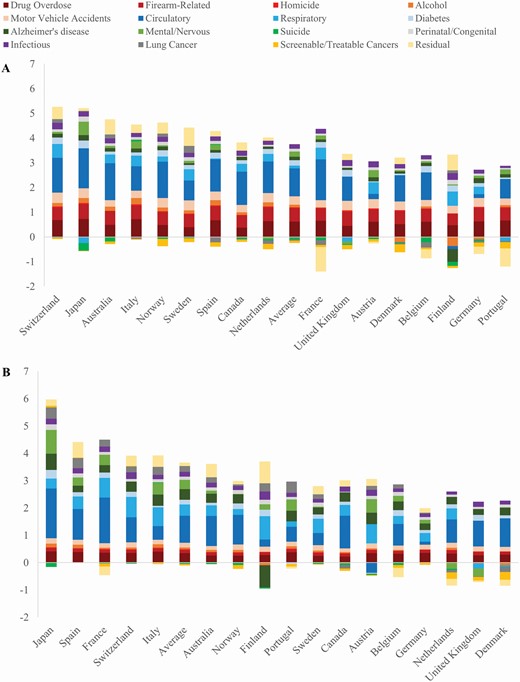

When you investigate the causes of the gap, you find (as you’d expect) a complex, multifactorial situation:

Contribution of 16 causes of death (years) to the U.S. shortfall in life expectancy at birth, men (A) and women (B), 2016.

Contribution of 16 causes of death (years) to the U.S. shortfall in life expectancy at birth, men (A) and women (B), 2016.

Certain disease categories pop up as you’d expected (e.g., circulatory), but what’s interesting is that you also see a number of social determinants of health2 occupying significant slices of the pie: injuries, for example — i.e., drug overdose, firearm-related deaths, motor vehicle accidents — accounting for 43% of American men’s life expectancy gap3.

These and other social determinants of health also feed back into the circulatory, respiratory, and diabetes slices. For example:

So then the question is how much of the gap can be explained by access to care and the efficacy of our healthcare system (in prevention, detection/diagnosis, and treatment) vis-à-vis the healthcare systems of peer countries?

This is tricky to nail down, but it’s certainly not zero: one particular study indicated that somewhere between 0.8 to 1.8 percent of deaths of Americans 25-65 could be attributed to the lack of health insurance5.

I would have thought that number would be higher—again, because healthcare spend and life expectancy are tightly coupled. Here you might say, well, if the US healthcare system weren’t fee-for-service and actually incented preventive care, then maybe there would be a larger gap between the insured and the uninsured, but interestingly, two recent studies show that while general health checks yielded good fruit (in increased chronic disease recognition and treatment and patient-reported outcomes, for example), they had “little or no effect on total mortality”67.

Mauricio Avendano and Ichiro Kawachi summarily declare in their 2014 article8:

Nevertheless, regardless of cross-national differences in access to quality medical care, the fact remains that the overwhelming contributors to the incidence of disease (e.g. poor health behaviors) operate largely outside the influence of medical care.

There’s much to be desired for the U.S. healthcare system—I, for one, am for single payer (even in the form of continued medicare expansion)—but in the final analysis it seems to have a lot less explanatory power on life expectancy than do guns, drugs, cars, and McDonald’s.

Cum hoc ergo propter hoc.

Happy Leap Day,

— ᴘ. ᴍ. ʙ.

U.S. Health Disadvantage: Causes and Potential Solutions, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Policy, Performance, and Evaluation; Last Reviewed: January 7, 2022. ↩

Rabah Kamal, Cynthia Cox, and Erik Blumenkranz. “What do we know about social determinants of health in the U.S. and comparable countries?” KFF, November 21, 2017. ↩

“Injuries (drug overdose, firearm-related deaths, motor vehicle accidents, homicide), circulatory diseases, and mental disorders/nervous system diseases (including Alzheimer’s disease) account for 86% and 67% of American men’s and women’s life expectancy shortfall, respectively.” Jessica Y Ho, Causes of America’s Lagging Life Expectancy: An International Comparative Perspective, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Volume 77, Issue Supplement_2, May 2022, Pages S117–S126. ↩

Preston SH, Stokes A. Contribution of Obesity to International Differences in Life Expectancy. Am J Public Health. November 2011. ↩

Wilper, Andrew P., Steffie Woolhandler, Karen E. Lasser, Danny McCormick, David H. Bor, and David U. Himmelstein. 2009. “Health Insurance and Mortality in US Adults.” American Journal of Public Health 99(12): 2289–2295. ↩

Krogsbøll LT, Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC. “General health checks in adults for reducing morbidity and mortality from disease.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 Jan;1:CD009009. ↩

Liss DT, Uchida T, Wilkes CL, Radakrishnan A, Linder JA. “General Health Checks in Adult Primary Care: A Review.” JAMA. 2021;325(22):2294–2306. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6524 ↩

Avendano, Mauricio, and Ichiro Kawachi. “Why do Americans have shorter life expectancy and worse health than do people in other high-income countries?” Annual Review of Public Health vol. 35 (2014): 307-25. ↩

First published: 2024-02-29 | tweet | cast | subscribe