Dead Poets Society, 1989.

Dead Poets Society, 1989. Dead Poets Society, 1989.

Dead Poets Society, 1989.

When I was in undergrad and I’d tell people I was majoring in Philosophy it wasn’t uncommon for me to get a reflexive Oh? What pray tell are you going to do with that?

A fair question, and the honest answer (in my head) was that I was hoping to emerge reasonably well-educated through the great tomes of western civilization and the tutelage of some wild-haired professors in tweed jackets. But that might be a bit toffee-nosed for someone who wasn’t high-born and would be workin’ for a livin’ after graduatin’. So I think I typically conveyed some vague intention to go into “business,” but I wasn’t overly anxious about it as there was this common refrain that you could and should study what you fancy (ars artis gratia).

Since the mid-20th century with the GI Bill, the university degree has been democratized, and for most students and their families the degree has not surprisingly represented an earnings premium; and a fortiori today, manifest in the sharp increase in STEM degrees and concomitant decline in the liberal arts1.

You can hardly blame the average American student/family for thinking about return on investment when tuition has been outpacing wages for years (cost side), and certain non-humanities degrees better align with certain lucrative careers (revenue side).

But ancient societies (e.g., classical Greece) placed great emphasis on cultivating virtue and excellence (arete) as the path to a fulfilling life. Aristotle, for example, argued that the highest good was eudaimonia, a life of nurturing wisdom, courage, justice, temperance, etc. that leads ultimately to happiness.

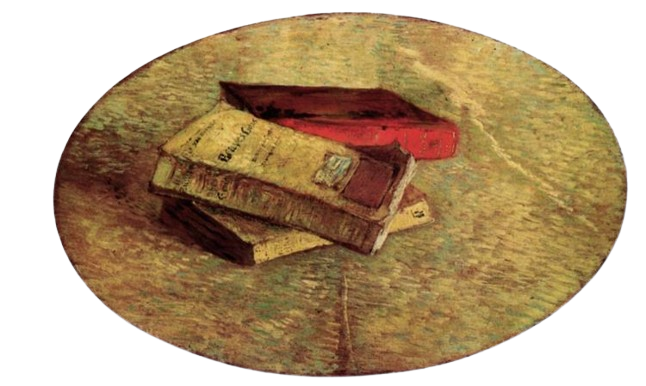

Still Life with Three Books. Vincent van Gogh, 1887.

Still Life with Three Books. Vincent van Gogh, 1887.

Contrast that to modern societies like that of the U.S. which prioritize safety and economic prosperity as the two paramount metrics of social success, because anything beyond these are subjective and matters of taste. This relegating of government to safety and prosperity is an Enlightenment “achievement” (i.e., not a new thing), but the difference is that in the 18th century, the assumption was that religion would fill in the gaps (regarding virtue). For example, “pursuit of happiness” in “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” didn’t need to be spelled out for folks since the assumption was that God-fearing people had their Christian faith to inform them about what is happiness—if not eudaimonia—and how might they attain it. But now that religion has been seriously attenuated in the West, the void produces a voluntaristic collision of wills, which leads straight to violence/war (Nietzsche et al. figured this out a long time ago).

Let’s enumerate the merits and faults of the liberal arts education:

Our democracy requires it. I often walked past this beautiful epigraph on the Boylston Street side of the Boston Public Library in Copley Square: THE COMMONWEALTH REQUIRES THE EDUCATION OF THE PEOPLE AS THE SAFEGUARD OF ORDER AND LIBERTY. Do we still believe this? If so, do we say it and impress it upon the public? Thomas Jefferson articulated a similar sentiment in one of his letters to Madison in 1787:

Above all things I hope the education of the common people will be attended to; convinced that on their good sense we may rely with the most security for the preservation of a due degree of liberty.

William Dean Howell answers the how:

All civilization comes through literature now, especially in our country. A Greek got his civilization by talking and looking, and in some measure a Parisian may still do it. But we, who live remote from history and monuments, we must read or we must barbarise.

Foundation for critical thinking and creativity. That sounds like something out of a brochure you might find in an admissions office, but I think it’s true and will be increasingly so as AI is able to take more and more of the tedious tasks off our plates (including things that currently command a premium like certain corporate lawyering tasks, for example).

First principles thinking. Having the important foundation to draw upon for thinking through complex issues and problems, which cut across history, philosophy, and other disciplines, is gold. Manly P. Hall makes the negative case (and bluntly):

The average person who goes to school has no idea why humanity exists. He has no idea concerning a spiritual factor in material existence. He has no general comprehension of the rules of life as these differ from the rules of social and political structures. He does not know where he came from. He does not know why he is here. And he has no idea where he’s going. And on this compound ignorance, we offer degrees and make brilliant scholars of the people who have never answered any of those questions. It is one of these amazing things that we have created a great hierarchy of well-lettered ignorance. We have made everything subservient not to wisdom, but to the passing advantages of the hour.

And late teens to early twenties is the time to do it before the system beats the curiosity out of you! There’s a short amount of time to read the great texts and study the great thinkers and become learned, so that you can begin to whittle things down to that which is truly valuable and that which is not; and begin to build mental models and frameworks to become a thinking person. Michael Oakeshott puts it well regarding college:

Here is a break in the tyrannical course of irreparable events; a period in which to look round upon the world and upon oneself without the sense of an enemy at one’s back or the insistent pressure to make up one’s mind; a moment in which to taste the mystery without the necessity of at once seeking a solution.

emollit mores nec sinit esse feros (i.e., a faithful study of the liberal arts humanizes character and permits it not to be cruel.) This should link to a future post about cancel culture and how we perceive good and evil, but essentially, the more learned people are, the more understanding. Example: voting in California which consists of picking yes or no across a dozen propositions, a terrible responsibility when you can’t possibly be adequately informed on each issue. Outside of taking someone’s else word for it with this endorsement or that voter guide, how do you evaluate said propositions on their own merits? Other political debates may end in “because the Constitution protects it!” but can we go beyond the Constitution or the testimony of a certain respected forefather and defend idea from a first principles standpoint. This is becoming increasingly difficult as we encounter and confront a fair amount of misinformation in the media landscape. Joyce Carol Oates said it well back in ‘06:

At a time when politics deals in distortions and half truths, truth is to be found in the liberal arts. There’s something afoot in this country and you are very much a part of it.

Specialization is for insects. While certain specialties may command a wage premium,

A great one from Robert Heinlein:

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

It’s true. When I conduct my which __ people, living or dead, would you invite to dinner? thought experiment, most I’d select are polymaths: Leonardo da Vinci, Isaac Newton2, Ben Franklin3, Lewis Carroll, G. K. Chesterton, Teddy Roosevelt, Martin Luther King Jr., et al.

Your history degree is cool until a recession. It’s true: when I graduated unemployment was at a 30-year low. Compare that to those who graduated during the ‘07-‘08 global financial crisis with a mountain of student loan debt and dire chances at finding gainful employment.

China is in favor of you getting a history degree. America is used to being on top economically, but global competition is only increasing, and many graduates will find it harder to have many good options in the future. It’s not exactly fair, but if you study history at Biola University and aren’t valedictorian, you may be kind of screwed. That’s a supercilious and facetious way to put it, but also true: you can get away with studying Renaissance Literature at Yale because you were certified (on your college acceptance letter) as having the intellectual horsepower to do all kinds of things in the future.

Taxpayers shouldn’t necessarily be subsidizing history degrees. Continuing from the last point, if the markets don’t demand it, we shouldn’t be footing the bill: i.e., the student loans, tax exempt statuses of universities, etc. America hasn’t invested in community colleges and vocational schools to the extent we need to, and a shifting of dollars could potentially incent the right behaviors. Again, there’s a narrative that everyone needs and deserves a four-year degree when the truth of the matter is that some students would be better suited with a more technical, and cost-effective education. Again, not fair, but if you or your family has the cash, there’s an art history degree available for you from a private college, and the 30-year ROI might not be there; but that’s not the concern of the state. The other approach would be to address the outrageous price of the four-year degree, but, unfortunately, as long as there’s substantial consumer surplus attached to the Ivy League degree, there’s not much to hold down the price—then the administrative bloat is just the result of the university optimizing for value capture over value creation (see also Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy).

Just get your history degree for a dollar fifty in late chahges from the public library. A recent episode of the Moment of Zen podcast4 featured an intriguing debate about liberal arts education, where someone glibly suggested, “you can literally just read [the classics]” on your own time. This echoes Grant Allen’s famous quip about not letting schooling interfere with education. While there’s some merit to this view—and, in fact, I’m that guy catching up on the literary classics he should have read years ago—my experience wrestling with the Divine Comedy (and similarly dense texts) has made me question this assumption: i.e., how much richer would my understanding be with an excellent professor and a lively class discussion? Moreover, this flippant argument about self-study could just as easily be turned against technical fields: why spend college years studying computer science when you can learn it independently through videos and AI tools, especially considering that programming languages and tools often become obsolete within a decade?

If you think about the arguments against, they’re centered around cost and ROI. Which is understandable, but also solvable, and, I’d argue, not as important as what’s at stake with the proper education of our nation. And so, for me the scales tip toward the liberal arts…but in a qualified way.

If we know what we want, we can do it all: kids emerge from the university fully formed and erudite, but also ready to jump into the workforce and contribute. Many schools nobly try to thread this needle by offering a thoughtfully constructed, highly rigorous and integrated liberal arts core curriculum (the Ratio Studiorum, if you will). It may not be such a bad runner-up to a liberal arts degree: it whets the appetites of those who will then delve into the world of ideas via Philosophy, English, etc.; and the accounting majors at least have the substratum that they’ll hopefully build upon whenever and however they might, and won’t have mortgaged the entirety of their undergraduate years to job training.

We’ve been talking about the university, but it’s important to go back to the primary grades, and think about our educational models, because how we learn and what we gear into starts at a young age. Chelsea Niemiec from the University of Dallas summarizes the issue5:

In the late 19th century, a series of progressive thinkers…set our country up to abandon a tried-and-true way of educating students in wisdom and virtue through the liberal arts and adopt a factory model meant to produce workers. The result? Plummeting reading and math scores and soaring anxiety and depression among students.

And so we have our son enrolled at a Catholic Classical school, which is compelling from the standpoint of its mission to weave together the liberal arts (via the trivium and so forth), hopefully engendering a love of learning and knowledge.

But additionally, for us, everything connects back to Jesus Christ (Logos), for Gloria enim Dei vivens homo (“The glory of God is man fully alive”), and we are alive insofar as we grow intellectually, morally, and spiritually through the pursuit of truth, beauty, and goodness.

Ad lucem,

— ᴘ. ᴍ. ʙ.

National Center for Education Statistics: from 2012 to 2020, graduates in the humanities declined by 30%. “The Decline of Liberal Arts and Humanities”, Wall Street Journal; March 28, 2023. ↩

Ironically, Ben Franklin had disdain for the liberal arts being useless, and set up UPenn to “train” students in business, etc. ↩

E28: Katherine Boyle and Mike Solana on Liberal Arts Debate, Tech Culture, and Saving San Francisco, Moment of Zen podcast; June 17, 2023. ↩

“The Decline of Liberal Arts and Humanities”, Wall Street Journal; March 28, 2023. ↩

First published: 2024-10-07 | tweet | cast | subscribe